Author: Vova Pyatsky

Translation: Roni Sherman and Marina Sherman

Translation Editor: Natasha Tsimbler

Chapters

Table of Contents The Practice of the Six Paramitas – Table of Contents

Introduction The Practice of the Six Paramitas – Introduction

1. The Practice of the Six Paramitas – The Paramita of Wisdom

2. The Practice of the Six Paramitas – The Paramita of Meditation

3. The Practice of the Six Paramitas – The Paramita of Diligence

4. The Practice of the Six Paramitas – The Paramita of Patience

5. The Practice of the Six Paramitas – The Paramita of Self-Restraint

6. The Practice of the Six Paramitas – The Paramita of Giving

4. The Paramita of Patience

Patience — is a state in which there is no painful sensitivity while there is vigilance. Therefore the paramita of patience — is the perfection of the inner observer, also called the inner Teacher. Reduction of painful sensitivity is achieved with correct attitude towards memory, while vigilance is developed thanks to correct understanding of the law of action and its outcomes. (Karma)

Memory

Everything which arises —

Arises from unmanifested tendencies,

Therefore in the incredible, bottomless world,

You won't find anything

Which would not consist of your memories.

Look at all of manifested existence as

A manifestation of your own memory,

And you'll be able to

Distinguish the illusory nature of all phenomena.

In an illusion, there is no ground to divide the mind into an “I” and a “world”.

Therefore distinguishing the illusory nature of existence is truly gracious!

Views of ourselves and the world

Cannot grow unabated once they

Are limited by differentiation of their illusory nature. Thanks to this, there is reduction of painful sensitivity.

Karma

Choice of action shapes the consciousness of the doer —

Such is the law of karma.

Wholesome choice leads to rebirth in the higher realms,

Unwholesome choice — in the realms of delusion.

The highest realms and highest form of birth — are those which allow the being to come in contact with the Teaching and even meet with true Teachers.

Such a birth is wholesome,

Even if the being

Was reborn in a place

Ruled by demons.

The lower realms and lower birth

Are those in which beings do not meet with the Teaching or Teachers

Who have attained the highest knowledge.

Such a lower birth may be

Outwardly pleasant,

But inwardly, it is poisonous.

A being, not having acquired a connection with the Teaching

And true Teachers

Might even be misled to

Believe in false teachers

And practice false teachings,

Leading to long-term suffering.

In those cases,

Even a world full of prosperity and wealth

Is one of the lower realms.

By reflecting this way,

You will develop vigilance,

Choosing what should be done

And what — should not.

Patience consists in rejecting the quest for impermanent things and turning the mind to the quest for permanent peace and liberation from ignorance.

Patience develops thanks to correct mindfulness of the everyday activities of the body, speech and mind. Watching them, we eliminate belief in their specialty and reduce the excitement from what is happening with them. This practice is presented in depth in Maitreya's Tantra.

Maitreya’s Teaching

Maitreya's Assembly

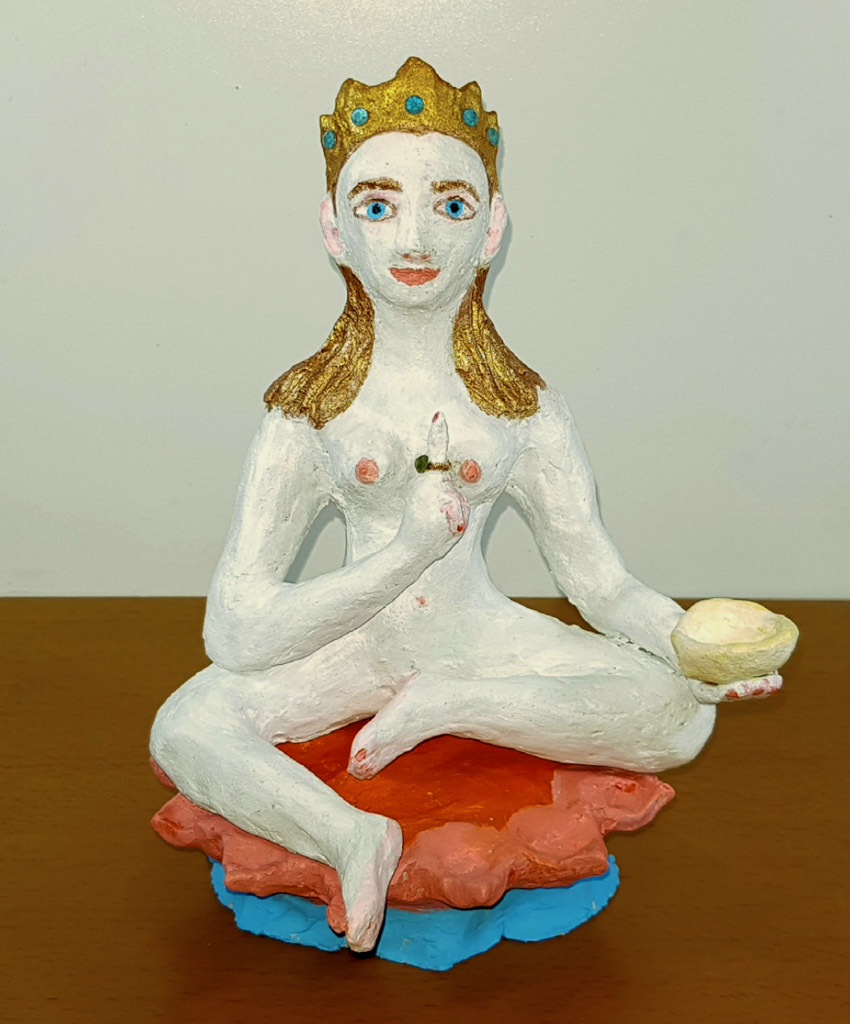

In the heavens, in a Pure Land, abides Buddha Maitreya, a friend to all beings.

One day, gods and demons came to him with offerings. The gods brought flowers, while the demons — thorns. They wanted to sit on opposite sides of Maitreya, but the Buddha stopped them. Each of you brought your own mind. These gifts — are the best you've got, since you identify yourself with them. Therefore you have all shown your devotion with the means available to you. Sit together.

After listening to Maitreya, the gods and demons sat together at his feet. Thereafter a garden full of beautiful roses blooming on slender thorn-covered stems appeared around their assembly. The gods and demons begged Maitreya to give them a teaching on enlightenment expressed in a single phrase so that they could follow the path without distraction. However, Maitreya shook his head and said: “the teaching cannot be expressed in a single phrase, since even in the ordinary world, in order to come from one place to another, we must use both legs.”

However the gods and demons did not despair. They began to accumulate virtue. The gods supported the existence of those going on the noble path, while the demons protected them from dangers. Having accumulated plenty of good deeds, the gods and demons returned to Maitreya with the same request. This time, he answered them: “I'll tell you a method that is transmitted in a single phrase. Thanks to it, you will behold the essence with the Eye of Wisdom.

All true teachings lead beings to understanding their pure nature unblemished by ignorance. Therefore whoever you are, a God, a demon or a human being, once your attention begins to focus on something, once but decisively tell yourself: “REMEMBER YOURSELF!” Do not try to catch the answer, but also do not occupy yourself with repetitive thoughts. Simply accumulate the power of this wish “REMEMBER YOURSELF” and observe the experiences arising in the mind, filtering out the vicious and cultivating the virtuous. Such is all of Dharma in a single phrase.

The Story of Dharmabhadra

The monk Dharmabharda worshiped Buddha Maitreya. Despite all his efforts, he could not grasp the essence of remembering himself. One day, Dharmabhadra found a scroll lying in the cesspool of a latrine. Dharmabhadra was surprised to discover Maitreya’s words in the inscriptions. The disciple wanted to pull out this manuscript but hesitated:

“If it's dumped in a latrine, it's probably useless.” Then Dharmabhadra thought otherwise: “Is my mind, unable to remember itself instantly like gods and protectors of Dharma do, not like a latrine? Maybe this scroll of Maitreya’s Teaching is a sign of compassion for me, a hidden gem of Dharma?” And Dharmabhadra pulled out the manuscript. At that same moment, he realized that the exercise of the instructions “REMEMBER YOURSELF” is very favorable when defecating and urinating, because during both of them, the strain which interferes with the attainment of peace is distinctly reduced.

Afterwards, Dharmabhadra went to the river with the scroll — to wash the parchment from impurities. As he started to wash the manuscript, he was noticed by laundresses who started to laugh at the monk clumsily messing around with the parchment soiled with impurities. From embarrassment, Dharmabhadra started to wash the parchment rapidly and in haste, not only washing away the impurities, but also washing away the text itself. Consequently, the manuscript became illegible. Seeing the fruits of his actions with regret, Dharmabhadra realized that a second favourable situation for remembering yourself is ablution.

Afterwards, laying out the manuscript to dry, Dharmabhadra stood beside and, repenting his haste, started to absentmindedly eat a loaf of bread. Crumbs fell down onto the manuscript, and suddenly sparrows swooped down. They started to cheerfully and excitedly chirp and fight over for the crumbs. At first, Dharmabhadra tried to shoo them away, but from this, even more crumbs from the bread squeezed in his hand fell down onto the manuscript, and the sparrows gathered in even greater numbers. At the sight of this spectacle, Dharmabhadra realized that the chirping and fussing of the sparrows was a reading of Maitreya's manuscript in the language of the Garudas. Then Dharmabhadra formulated a rule: “Remember yourself when eating.”

The story of the thief

Practicing Maitreya's teaching, Dhamabhadra also taught other beings. One day, a thief got wind of the incredible manuscript kept by Dharmabhadra. He decided to steal this precious relic and began to closely watch Dhamabhadra and his daily routine, trying to determine the most favorable moment to carry out his plan. The thief was perplexed by Dharmabhadra's vigilant behavior and his persistent attention towards Maitreya's manuscript. Nevertheless, the thief knew that impatience would never allow him to come close to fulfilling his objective and he learned to relaxedly wait for the right moment by destroying the strain and abruptness in his mind that could give away his plan.

At last, an opportune moment presented itself, and the thief broke into Dharmabhadra’s abode. The manuscript lay in plain sight. The thief stretched out his hand to it, to take, but suddenly realized that by stealing from Dharmabhadra, he was stealing from himself. By watching Dharmabhadra's behaviour for a long time, empathetic and compassionate, the thief purified his mind and realized the Presence of the Teacher in his own heart. After this experience, the thief took refuge at the feet of Buddha Dharmabhadra and became his disciple. Skilfully practicing Maitreyas Teaching, he added three commandments to it: remember yourself when going to bed, remember yourself when waking up, and remember yourself when desire overwhelms you.

The Teacher instructed: “When falling asleep, the mind is kidnapped by the experience of the silence of the mind. Find the wisdom that cannot be stolen! When waking up, the mind is kidnapped by the experience of the clarity of the senses. Establish yourself in the wisdom that cannot be stolen! When the mind is overwhelmed with desire, it is kidnapped by the experience of bliss. Abide in the wisdom that cannot be stolen!

The nature of the Tathagatha, suchness, cannot be kidnapped because it does not fall into the extremes of 1) appearance and disappearance, inherent to the experience of the silence of the mind 2) growth and decline, inherent to the experience of clarity ; 3) existence and non-existence

(Possession of something or loss), inherent to the experience of bliss.

The story of the prostitute

The former thief deeply realized the Teaching and transmitted it to other beings. One day, a prostitute came to him and offered him her services. To this, the Teacher replied: “I don't have decent pay for your work”. Then the prostitute objected: “No. You've got the Teaching”. Upon hearing these words, the Teacher began transmitting instructions to her, and she managed to apply them to her life, leaving past suffering. Having become a disciple, she provided for her livelihood with work in the kitchen, and, slowly having developed the siddhis of transferring the mind into higher realms, attained Awakening. Having become a Preceptress, she added three of her own commandments to the instructions: remember yourself when expecting something, remember yourself when acting subject to the volition of another, and remember yourself when dressing and undressing.

The Precepetress said: “When I expected clients, my mind was overtaken by hope and fear. But somehow I realized that the only client who would come for certain — was death, and I turned to the Teacher. My clients often abused me, hit me and bullied me. However, understanding the suffering of my own mind, I learned that no vilain bullied me, humiliated me and hurt me so much as have the constant tormentors of my own mind — desires. Then I began to happily practice the Teaching. In my line of work, when I was a prostitute, pay was determined by the number of times I undressed and dressed to undress again. One day, I took off the clothes of the sense of “I” and put on the clothes of Recognizing the Emptiness of the Mind. After that, I stopped living in need and fear.”

Let good be!

The path of remembering ourselves

The key question in the practice of remembering — is finding the mind. We can recognize our mind just as we recognize our body of which we say “I”.

However, recognizing the sense of “I” is a dream of ignorance, while recognizing the mind is awakening. During practice, the difference between impermanent beliefs about our “self” and the permanence of a pure mind is comprehended. A pure mind has no need in a sense of “I”, just as a man with healthy legs has no need in the use of crutches.

Initially, remembering ourselves is a simple recollection of how we were in similar situations or performed similar actions in the past. Thanks to this recollection, practitioners begin to better see the differences and similarities in the actions and situations that occur in their lives.

Then there is differentiation of suffering and its causes, which manifest themselves in all actions and situations. It becomes clear that absent-mindedness, the excitation of the mind and ignorance give rise to one another. There is development of concentration, purification of the mind and enlightenment. Remembering leads to understanding that all notion of “I” is associated with suffering. As a result of this understanding, there is extinction of the sense of “I” and rejection of attachment to name and body.

The Ten Turning Points of Practice

1. Maitreya's Rose

Situations of choice between wholesome and unwholesome behavior are the first turning point in the practice of remembering ourselves. By thinking, “Everybody gives the best of what they have at the moment”, practitioners end hostility and attachment. Once hostility and attachment end, choice of behaviour is made based on noble motives, and not based on fear and desire. Practitioners think like this: “Disgust is more disgusting than the being or phenomenon which causes it. Because contact with these phenomena and beings is impermanent and would eventually come to an end, but disgust would accompany me from one incarnation to the next. Unpleasant phenomena — are the external thorns. My disgust — is an internal, deeply-seated thorn. I'll use the external thorn to extract the internal!” They also think: “The mind is more pleasant than everything it desires. After all, even a great king who possesses wealth, luxury and power can enjoy them only as long as his mind empowers the senses. How is a corpse in a pigsty different from a corpse in a castle? I'll focus on the bliss, power and clarity of the mind itself without getting distracted by the reflections its light gives rise to in the senses and thought”.

A mind undisturbed by attachment and hostility (disgust) takes the form of the central channel — the road by which all the liberated pass. Practitioners reinforce this understanding of the central channel by visualizing Maitreya's Rose.

Maitreya's Rose, passing in the practitioner's body from the perineum to the crown, is covered with thorns in the practitioner's area of the body and neck, and is crowned with delicate petals in the area of the cerebrum. The thorns contain stress and weakness: stress — in the sharp spines and weakness — in the wide base. As a result of containment, there is the experience of clarity. The petals transform the confusion of the mind into the experience of bliss. The stem of the rose expresses the experience of the silence of the mind. As a whole, Maitreya’s Rose — is Buddha nature, and its scent — is Dharma. All the phenomena of the world — are like dew on the petals of this rose — appearing suddenly and disappearing without a trace.

2. The precious scroll

Defecation and urination — is the second turning point. It is the practice of worshiping the Buddha of our own mind. When we make an offering to the Buddha, we experience joy and relief. However, when we make an offering to a statue or image of the Buddha, we still have uncertainty — are we not deceiving ourselves? How much does our symbolic offering contribute to the accumulation of merit? However, defecation and urination, which are necessary conditions for life, bring genuine relief and joy which have no need for inspection. Those relief and joy are nothing other than the enlightenment of Dharmabhadra who found Maitreya's scroll in the cesspool.

Our body — is Maitreya’s manuscript, which we find in the cesspool of the darkened activity of our own mind. During defecation, urination and perspiration, our bodily winds are most perceptible. That makes it possible to clearly recognize volition — the power to make and realize decisions. The direction of volition is determined by past acts and leads beings to rebirth in the realm corresponding to this direction after the dissolution of the body. Therefore the points of defecation, urination and perspiration are very favourable for the inception of wholesome aspiration.

3. The mind and body, the inner and outer, birth and death

Ablution — is the third turning point. Bathing with water cleans the surface of the body. Wholesome instructions wash beings from inside. During ablution, one should perceive that the body — is the outer part of the scroll of Maitreya’s instructions, while the mind — the inner. Dharmabhadra washes the scroll, but damages the text. The disappeared part of the text appears in the laughter of the laundresses. Dharmabhadra is embarrassed, but this embarrassment signifies correct understanding of the preacher of the laundresses (patroness-goddesses), it leads Dharmabhadra’s strong mentality to repentance and rejection of vicious qualities. Dharmabhadra repents his haste and eats a piece of bread — a symbol of health and awakening.

Dharmabhadra said: “during ablution, the body is naked like during birth. The mind likewise becomes naked during death. Purify this nakedness from delusions!”

4. The prajnaparamita mantra

Eating — is the fourth turning point. The teeth in our mouth are like sparrow beaks. When we taste, chew, swallow — our mouth recites the Prajnaparamita mantra (the mantra of perfect wisdom) in the language of the Garudas (winged gods of wind). By remembering ourselves while eating, we feed bodily winds (pranas).

While eating, beings are least conscious. They are seized by taste and the other qualities of food. The mind expresses its restlessness, which is like that of a flock of sparrows.

Dharmabhadra said: “See food as the offering of thorns the demons made to Maitreya. Eating thorns makes camels and donkeys the most hardy animals. Attachment to food — is a thorn. Aversion to food — is a thorn. Indifference — is a thorn. Hunger — is a thorn. Overeating, which causes clouding of the consciousness — is a thorn. With the thorn of food, remove the splinter of restless insatiability, and then you will eat as much as needed to maintain the health and strength of the body.”

5. The Recognition of Dharmabhadra

Falling asleep — is the fifth turning point. The thief said: “Correct falling asleep — is watching Dharmabhadra indulging in meditation. As we fall asleep, Dhramabhadra remains watchful in his meditation. He knows the approach of sleep, the point of contact with the state of sleep, and resting in sleep. The approach of sleep — is Dharmabhadra’s meditation hall. Contact with the state of sleep — is his calm and steady posture. Resting in sleep — is his eye directed inward. What does Dharmabhadra look like outwardly? Sometimes he is a man, and sometimes — a woman. Sometimes he is an old man, and sometimes — a child. Sometimes he is a God, and sometimes — an animal. Sometimes he walks, sometimes he stands, sometimes he sits, and sometimes — he lies down. He — is the emptiness of your own mind that is assuming various guises.”

6. The meeting of the mind with itself

Waking up — is the sixth turning point. When we wake up from sleep, a thousand impulses, a thousand voices and a thousand views wake up with us. They wake us up, and we wake them up in our own consciousness. Perceptions which appear when waking up from sleep should be seen as rain from the petals of those flowers which were offered to Maitreya. That's how depressing mood is overcome.

The thief said: “I was very tense when I kept an eye on Dharmabhadra. So that the tension did not give away my presence, I had to relax. For that, I focused on the sense of peace emanating from Dharmabhadra. Finally, I discovered Dharmabhadra in my own heart. Our meeting became the meeting of the mind with itself.”

7. The sameness of desire and suffering

Being overcome by desire — is the seventh turning point. It is like a splinter, a thorn embedded in our finger. By seeing the senses as a finger with which the mind touches existence, we do not swiftly bring perceptions close to the heart. The rise of the occupation of the senses and their liberation is like the pricking of a finger on a thorn and the jerking away from it.

The thief said: “Being overcome by desire is like lying on a nail-studded bed. It is like chewing sand. It is like a speck that got into the eye. It is like the smell of a corpse. Unawakened beings consider desire and suffering to be different from one another. Buddhas see their sameness.”

8. Expectation

Expectation — is the eighth turning point. The Buddha in our mind has no one and no reason to expect. Nevertheless, the mind, without noticing the Buddha within itself, expects the realization of desires or fears bad changes. Turning to itself, the mind puts an end to all expectations. That means that a decision is made that good changes must come from within as a result of purifying the mind from vices.

The Perceptress said: A tree which has reached deep, moist layers of soil with its roots ceases to be dependent on rain. The tree — is your mind. The deep, moist layers of soil — are the Immeasurable Feelings hidden behind the dry and lifeless soil of the sense of “I”. The rain from which independence is gained — is the perceptions of the senses and the events of the external world.

9. Obedience to another's volition

Obedience to another's volition — is the ninth turning point. Circumstances which constrain people are perceived by them as another's volition. Such perception of adversity and hardship reinforces the sense of “I”, which is built from beliefs about our own defeats and victories over an imaginary adversary.

The Perceptress sang:

Did I have my own volition?

The gem for which I suffered,

Desiring freedom from painful circumstances?

No, it never existed.

This last bondage fought another bondage.

I took the suffering I had the time to get used to

for my own volition.

I thought that I knew myself —

but discovered in my “I”

Only the warmth of another's breath,

The echo of another's cries and whisper.

Now, I feel those desires I once kept

only as the

Touch of the icy hands of the dead.

10. Changing clothes

Changing clothes — is the tenth turning point of practice. Changes of behaviour, senses and thought — are inner changes of clothes. Remembering ourselves when changing clothes — means seeing ourselves as being born and dying, recognizing and forgetting, believing in something and becoming disenchanted. Thus we become free of clinging to the states of the body, senses and consciousness.

The tenth turning point of practice is principal in renouncing the thought "That is I. That is forever mine” about phenomena, senses, thoughts, aspirations and states of consciousness. By remembering themselves during external and internal changes of clothes, practitioners of the noble path see that there is nothing either outside or inside which could be called “myself” or “forever mine”.

Taking Refuge in the Triple Gem

The Three keepers of Maitreya’s lineage (Dharmabhadra, the thief and the prostitute) embody, respectively, taking refuge in the triple gem (Buddha nature, the Teaching and Sangha).

The mind is concerned about three factors: 1) fear of loss, which comes down to fear of death 2) sensual thirst 3) darkened emotions, which are mental chewing gum.

From fear of death, we take refuge in our own unborn mind (Buddha). For the unborn mind, death — is a shallow stream it crosses without losing itself. We think about the unborn mind as blissful luminiferous emptiness that is unperplexed by anything. There are three steps to taking this view: 1) taking refuge in Buddha nature on the basis of authoritative opinions (of the Buddha, other sages and one's own teacher); 2) taking refuge in Buddha nature on the basis of conclusions arising from observations and practice (for example, the experiences which evidence the supremacy of energy over form; expansion of the consciousness; clairvoyance, etc. 3) taking refuge in the Buddha of our own mind as a result of developing supermundane wisdom. The point of all three steps — is remembering that the basis of the mind is permanent and steadfast.

From thirst, we take refuge in the Dharma. When beings unskillfully seek satisfaction in impermanent phenomena, ultimately this satisfaction turns into dissatisfaction. But Dharma brings continued satisfaction resulting from liberation from the triple thirst.

From darkened desires (mental chewing gum), we take refuge in the Sangha. Since in the Sangha we develop infinite feelings, which end darkened states, it is the Sangha which gives us refuge from desires. Whereas in communication with relatively distant people we often act like camels, spitting our mental chewing gum all over our interlocutor's face while fencing off from his or her feelings and thoughts, it is impossible to carry out this action in the Sangha. Here our chewing gum is already well-known to everyone, and for wholesome communication, we need something greater and more meaningful — openness and care.

Let good be!

Author

Author: Vova Pyatsky

Translation: Roni Sherman and Marina Sherman

Translation Editor: Natasha Tsimbler

Chapters

Table of Contents The Practice of the Six Paramitas – Table of Contents

Introduction The Practice of the Six Paramitas – Introduction

1. The Practice of the Six Paramitas – The Paramita of Wisdom

2. The Practice of the Six Paramitas – The Paramita of Meditation

3. The Practice of the Six Paramitas – The Paramita of Diligence

4. The Practice of the Six Paramitas – The Paramita of Patience

5. The Practice of the Six Paramitas – The Paramita of Self-Restraint

6. The Practice of the Six Paramitas – The Paramita of Giving

4. The Paramita of Patience

Patience — is a state in which there is no painful sensitivity while there is vigilance. Therefore the paramita of patience — is the perfection of the inner observer, also called the inner Teacher. Reduction of painful sensitivity is achieved with correct attitude towards memory, while vigilance is developed thanks to correct understanding of the law of action and its outcomes. (Karma)

Memory

Everything which arises —

Arises from unmanifested tendencies,

Therefore in the incredible, bottomless world,

You won't find anything

Which would not consist of your memories.

Look at all of manifested existence as

A manifestation of your own memory,

And you'll be able to

Distinguish the illusory nature of all phenomena.

In an illusion, there is no ground to divide the mind into an “I” and a “world”.

Therefore distinguishing the illusory nature of existence is truly gracious!

Views of ourselves and the world

Cannot grow unabated once they

Are limited by differentiation of their illusory nature. Thanks to this, there is reduction of painful sensitivity.

Karma

Choice of action shapes the consciousness of the doer —

Such is the law of karma.

Wholesome choice leads to rebirth in the higher realms,

Unwholesome choice — in the realms of delusion.

The highest realms and highest form of birth — are those which allow the being to come in contact with the Teaching and even meet with true Teachers.

Such a birth is wholesome,

Even if the being

Was reborn in a place

Ruled by demons.

The lower realms and lower birth

Are those in which beings do not meet with the Teaching or Teachers

Who have attained the highest knowledge.

Such a lower birth may be

Outwardly pleasant,

But inwardly, it is poisonous.

A being, not having acquired a connection with the Teaching

And true Teachers

Might even be misled to

Believe in false teachers

And practice false teachings,

Leading to long-term suffering.

In those cases,

Even a world full of prosperity and wealth

Is one of the lower realms.

By reflecting this way,

You will develop vigilance,

Choosing what should be done

And what — should not.

Patience consists in rejecting the quest for impermanent things and turning the mind to the quest for permanent peace and liberation from ignorance.

Patience develops thanks to correct mindfulness of the everyday activities of the body, speech and mind. Watching them, we eliminate belief in their specialty and reduce the excitement from what is happening with them. This practice is presented in depth in Maitreya's Tantra.

Maitreya’s Teaching

Maitreya's Assembly

In the heavens, in a Pure Land, abides Buddha Maitreya, a friend to all beings.

One day, gods and demons came to him with offerings. The gods brought flowers, while the demons — thorns. They wanted to sit on opposite sides of Maitreya, but the Buddha stopped them. Each of you brought your own mind. These gifts — are the best you've got, since you identify yourself with them. Therefore you have all shown your devotion with the means available to you. Sit together.

After listening to Maitreya, the gods and demons sat together at his feet. Thereafter a garden full of beautiful roses blooming on slender thorn-covered stems appeared around their assembly. The gods and demons begged Maitreya to give them a teaching on enlightenment expressed in a single phrase so that they could follow the path without distraction. However, Maitreya shook his head and said: “the teaching cannot be expressed in a single phrase, since even in the ordinary world, in order to come from one place to another, we must use both legs.”

However the gods and demons did not despair. They began to accumulate virtue. The gods supported the existence of those going on the noble path, while the demons protected them from dangers. Having accumulated plenty of good deeds, the gods and demons returned to Maitreya with the same request. This time, he answered them: “I'll tell you a method that is transmitted in a single phrase. Thanks to it, you will behold the essence with the Eye of Wisdom.

All true teachings lead beings to understanding their pure nature unblemished by ignorance. Therefore whoever you are, a God, a demon or a human being, once your attention begins to focus on something, once but decisively tell yourself: “REMEMBER YOURSELF!” Do not try to catch the answer, but also do not occupy yourself with repetitive thoughts. Simply accumulate the power of this wish “REMEMBER YOURSELF” and observe the experiences arising in the mind, filtering out the vicious and cultivating the virtuous. Such is all of Dharma in a single phrase.

The Story of Dharmabhadra

The monk Dharmabharda worshiped Buddha Maitreya. Despite all his efforts, he could not grasp the essence of remembering himself. One day, Dharmabhadra found a scroll lying in the cesspool of a latrine. Dharmabhadra was surprised to discover Maitreya’s words in the inscriptions. The disciple wanted to pull out this manuscript but hesitated:

“If it's dumped in a latrine, it's probably useless.” Then Dharmabhadra thought otherwise: “Is my mind, unable to remember itself instantly like gods and protectors of Dharma do, not like a latrine? Maybe this scroll of Maitreya’s Teaching is a sign of compassion for me, a hidden gem of Dharma?” And Dharmabhadra pulled out the manuscript. At that same moment, he realized that the exercise of the instructions “REMEMBER YOURSELF” is very favorable when defecating and urinating, because during both of them, the strain which interferes with the attainment of peace is distinctly reduced.

Afterwards, Dharmabhadra went to the river with the scroll — to wash the parchment from impurities. As he started to wash the manuscript, he was noticed by laundresses who started to laugh at the monk clumsily messing around with the parchment soiled with impurities. From embarrassment, Dharmabhadra started to wash the parchment rapidly and in haste, not only washing away the impurities, but also washing away the text itself. Consequently, the manuscript became illegible. Seeing the fruits of his actions with regret, Dharmabhadra realized that a second favourable situation for remembering yourself is ablution.

Afterwards, laying out the manuscript to dry, Dharmabhadra stood beside and, repenting his haste, started to absentmindedly eat a loaf of bread. Crumbs fell down onto the manuscript, and suddenly sparrows swooped down. They started to cheerfully and excitedly chirp and fight over for the crumbs. At first, Dharmabhadra tried to shoo them away, but from this, even more crumbs from the bread squeezed in his hand fell down onto the manuscript, and the sparrows gathered in even greater numbers. At the sight of this spectacle, Dharmabhadra realized that the chirping and fussing of the sparrows was a reading of Maitreya's manuscript in the language of the Garudas. Then Dharmabhadra formulated a rule: “Remember yourself when eating.”

The story of the thief

Practicing Maitreya's teaching, Dhamabhadra also taught other beings. One day, a thief got wind of the incredible manuscript kept by Dharmabhadra. He decided to steal this precious relic and began to closely watch Dhamabhadra and his daily routine, trying to determine the most favorable moment to carry out his plan. The thief was perplexed by Dharmabhadra's vigilant behavior and his persistent attention towards Maitreya's manuscript. Nevertheless, the thief knew that impatience would never allow him to come close to fulfilling his objective and he learned to relaxedly wait for the right moment by destroying the strain and abruptness in his mind that could give away his plan.

At last, an opportune moment presented itself, and the thief broke into Dharmabhadra’s abode. The manuscript lay in plain sight. The thief stretched out his hand to it, to take, but suddenly realized that by stealing from Dharmabhadra, he was stealing from himself. By watching Dharmabhadra's behaviour for a long time, empathetic and compassionate, the thief purified his mind and realized the Presence of the Teacher in his own heart. After this experience, the thief took refuge at the feet of Buddha Dharmabhadra and became his disciple. Skilfully practicing Maitreyas Teaching, he added three commandments to it: remember yourself when going to bed, remember yourself when waking up, and remember yourself when desire overwhelms you.

The Teacher instructed: “When falling asleep, the mind is kidnapped by the experience of the silence of the mind. Find the wisdom that cannot be stolen! When waking up, the mind is kidnapped by the experience of the clarity of the senses. Establish yourself in the wisdom that cannot be stolen! When the mind is overwhelmed with desire, it is kidnapped by the experience of bliss. Abide in the wisdom that cannot be stolen!

The nature of the Tathagatha, suchness, cannot be kidnapped because it does not fall into the extremes of 1) appearance and disappearance, inherent to the experience of the silence of the mind 2) growth and decline, inherent to the experience of clarity ; 3) existence and non-existence

(Possession of something or loss), inherent to the experience of bliss.

The story of the prostitute

The former thief deeply realized the Teaching and transmitted it to other beings. One day, a prostitute came to him and offered him her services. To this, the Teacher replied: “I don't have decent pay for your work”. Then the prostitute objected: “No. You've got the Teaching”. Upon hearing these words, the Teacher began transmitting instructions to her, and she managed to apply them to her life, leaving past suffering. Having become a disciple, she provided for her livelihood with work in the kitchen, and, slowly having developed the siddhis of transferring the mind into higher realms, attained Awakening. Having become a Preceptress, she added three of her own commandments to the instructions: remember yourself when expecting something, remember yourself when acting subject to the volition of another, and remember yourself when dressing and undressing.

The Precepetress said: “When I expected clients, my mind was overtaken by hope and fear. But somehow I realized that the only client who would come for certain — was death, and I turned to the Teacher. My clients often abused me, hit me and bullied me. However, understanding the suffering of my own mind, I learned that no vilain bullied me, humiliated me and hurt me so much as have the constant tormentors of my own mind — desires. Then I began to happily practice the Teaching. In my line of work, when I was a prostitute, pay was determined by the number of times I undressed and dressed to undress again. One day, I took off the clothes of the sense of “I” and put on the clothes of Recognizing the Emptiness of the Mind. After that, I stopped living in need and fear.”

Let good be!

The path of remembering ourselves

The key question in the practice of remembering — is finding the mind. We can recognize our mind just as we recognize our body of which we say “I”.

However, recognizing the sense of “I” is a dream of ignorance, while recognizing the mind is awakening. During practice, the difference between impermanent beliefs about our “self” and the permanence of a pure mind is comprehended. A pure mind has no need in a sense of “I”, just as a man with healthy legs has no need in the use of crutches.

Initially, remembering ourselves is a simple recollection of how we were in similar situations or performed similar actions in the past. Thanks to this recollection, practitioners begin to better see the differences and similarities in the actions and situations that occur in their lives.

Then there is differentiation of suffering and its causes, which manifest themselves in all actions and situations. It becomes clear that absent-mindedness, the excitation of the mind and ignorance give rise to one another. There is development of concentration, purification of the mind and enlightenment. Remembering leads to understanding that all notion of “I” is associated with suffering. As a result of this understanding, there is extinction of the sense of “I” and rejection of attachment to name and body.

The Ten Turning Points of Practice

1. Maitreya's Rose

Situations of choice between wholesome and unwholesome behavior are the first turning point in the practice of remembering ourselves. By thinking, “Everybody gives the best of what they have at the moment”, practitioners end hostility and attachment. Once hostility and attachment end, choice of behaviour is made based on noble motives, and not based on fear and desire. Practitioners think like this: “Disgust is more disgusting than the being or phenomenon which causes it. Because contact with these phenomena and beings is impermanent and would eventually come to an end, but disgust would accompany me from one incarnation to the next. Unpleasant phenomena — are the external thorns. My disgust — is an internal, deeply-seated thorn. I'll use the external thorn to extract the internal!” They also think: “The mind is more pleasant than everything it desires. After all, even a great king who possesses wealth, luxury and power can enjoy them only as long as his mind empowers the senses. How is a corpse in a pigsty different from a corpse in a castle? I'll focus on the bliss, power and clarity of the mind itself without getting distracted by the reflections its light gives rise to in the senses and thought”.

A mind undisturbed by attachment and hostility (disgust) takes the form of the central channel — the road by which all the liberated pass. Practitioners reinforce this understanding of the central channel by visualizing Maitreya's Rose.

Maitreya's Rose, passing in the practitioner's body from the perineum to the crown, is covered with thorns in the practitioner's area of the body and neck, and is crowned with delicate petals in the area of the cerebrum. The thorns contain stress and weakness: stress — in the sharp spines and weakness — in the wide base. As a result of containment, there is the experience of clarity. The petals transform the confusion of the mind into the experience of bliss. The stem of the rose expresses the experience of the silence of the mind. As a whole, Maitreya’s Rose — is Buddha nature, and its scent — is Dharma. All the phenomena of the world — are like dew on the petals of this rose — appearing suddenly and disappearing without a trace.

2. The precious scroll

Defecation and urination — is the second turning point. It is the practice of worshiping the Buddha of our own mind. When we make an offering to the Buddha, we experience joy and relief. However, when we make an offering to a statue or image of the Buddha, we still have uncertainty — are we not deceiving ourselves? How much does our symbolic offering contribute to the accumulation of merit? However, defecation and urination, which are necessary conditions for life, bring genuine relief and joy which have no need for inspection. Those relief and joy are nothing other than the enlightenment of Dharmabhadra who found Maitreya's scroll in the cesspool.

Our body — is Maitreya’s manuscript, which we find in the cesspool of the darkened activity of our own mind. During defecation, urination and perspiration, our bodily winds are most perceptible. That makes it possible to clearly recognize volition — the power to make and realize decisions. The direction of volition is determined by past acts and leads beings to rebirth in the realm corresponding to this direction after the dissolution of the body. Therefore the points of defecation, urination and perspiration are very favourable for the inception of wholesome aspiration.

3. The mind and body, the inner and outer, birth and death

Ablution — is the third turning point. Bathing with water cleans the surface of the body. Wholesome instructions wash beings from inside. During ablution, one should perceive that the body — is the outer part of the scroll of Maitreya’s instructions, while the mind — the inner. Dharmabhadra washes the scroll, but damages the text. The disappeared part of the text appears in the laughter of the laundresses. Dharmabhadra is embarrassed, but this embarrassment signifies correct understanding of the preacher of the laundresses (patroness-goddesses), it leads Dharmabhadra’s strong mentality to repentance and rejection of vicious qualities. Dharmabhadra repents his haste and eats a piece of bread — a symbol of health and awakening.

Dharmabhadra said: “during ablution, the body is naked like during birth. The mind likewise becomes naked during death. Purify this nakedness from delusions!”

4. The prajnaparamita mantra

Eating — is the fourth turning point. The teeth in our mouth are like sparrow beaks. When we taste, chew, swallow — our mouth recites the Prajnaparamita mantra (the mantra of perfect wisdom) in the language of the Garudas (winged gods of wind). By remembering ourselves while eating, we feed bodily winds (pranas).

While eating, beings are least conscious. They are seized by taste and the other qualities of food. The mind expresses its restlessness, which is like that of a flock of sparrows.

Dharmabhadra said: “See food as the offering of thorns the demons made to Maitreya. Eating thorns makes camels and donkeys the most hardy animals. Attachment to food — is a thorn. Aversion to food — is a thorn. Indifference — is a thorn. Hunger — is a thorn. Overeating, which causes clouding of the consciousness — is a thorn. With the thorn of food, remove the splinter of restless insatiability, and then you will eat as much as needed to maintain the health and strength of the body.”

5. The Recognition of Dharmabhadra

Falling asleep — is the fifth turning point. The thief said: “Correct falling asleep — is watching Dharmabhadra indulging in meditation. As we fall asleep, Dhramabhadra remains watchful in his meditation. He knows the approach of sleep, the point of contact with the state of sleep, and resting in sleep. The approach of sleep — is Dharmabhadra’s meditation hall. Contact with the state of sleep — is his calm and steady posture. Resting in sleep — is his eye directed inward. What does Dharmabhadra look like outwardly? Sometimes he is a man, and sometimes — a woman. Sometimes he is an old man, and sometimes — a child. Sometimes he is a God, and sometimes — an animal. Sometimes he walks, sometimes he stands, sometimes he sits, and sometimes — he lies down. He — is the emptiness of your own mind that is assuming various guises.”

6. The meeting of the mind with itself

Waking up — is the sixth turning point. When we wake up from sleep, a thousand impulses, a thousand voices and a thousand views wake up with us. They wake us up, and we wake them up in our own consciousness. Perceptions which appear when waking up from sleep should be seen as rain from the petals of those flowers which were offered to Maitreya. That's how depressing mood is overcome.

The thief said: “I was very tense when I kept an eye on Dharmabhadra. So that the tension did not give away my presence, I had to relax. For that, I focused on the sense of peace emanating from Dharmabhadra. Finally, I discovered Dharmabhadra in my own heart. Our meeting became the meeting of the mind with itself.”

7. The sameness of desire and suffering

Being overcome by desire — is the seventh turning point. It is like a splinter, a thorn embedded in our finger. By seeing the senses as a finger with which the mind touches existence, we do not swiftly bring perceptions close to the heart. The rise of the occupation of the senses and their liberation is like the pricking of a finger on a thorn and the jerking away from it.

The thief said: “Being overcome by desire is like lying on a nail-studded bed. It is like chewing sand. It is like a speck that got into the eye. It is like the smell of a corpse. Unawakened beings consider desire and suffering to be different from one another. Buddhas see their sameness.”

8. Expectation

Expectation — is the eighth turning point. The Buddha in our mind has no one and no reason to expect. Nevertheless, the mind, without noticing the Buddha within itself, expects the realization of desires or fears bad changes. Turning to itself, the mind puts an end to all expectations. That means that a decision is made that good changes must come from within as a result of purifying the mind from vices.

The Perceptress said: A tree which has reached deep, moist layers of soil with its roots ceases to be dependent on rain. The tree — is your mind. The deep, moist layers of soil — are the Immeasurable Feelings hidden behind the dry and lifeless soil of the sense of “I”. The rain from which independence is gained — is the perceptions of the senses and the events of the external world.

9. Obedience to another's volition

Obedience to another's volition — is the ninth turning point. Circumstances which constrain people are perceived by them as another's volition. Such perception of adversity and hardship reinforces the sense of “I”, which is built from beliefs about our own defeats and victories over an imaginary adversary.

The Perceptress sang:

Did I have my own volition?

The gem for which I suffered,

Desiring freedom from painful circumstances?

No, it never existed.

This last bondage fought another bondage.

I took the suffering I had the time to get used to

for my own volition.

I thought that I knew myself —

but discovered in my “I”

Only the warmth of another's breath,

The echo of another's cries and whisper.

Now, I feel those desires I once kept

only as the

Touch of the icy hands of the dead.

10. Changing clothes

Changing clothes — is the tenth turning point of practice. Changes of behaviour, senses and thought — are inner changes of clothes. Remembering ourselves when changing clothes — means seeing ourselves as being born and dying, recognizing and forgetting, believing in something and becoming disenchanted. Thus we become free of clinging to the states of the body, senses and consciousness.

The tenth turning point of practice is principal in renouncing the thought "That is I. That is forever mine” about phenomena, senses, thoughts, aspirations and states of consciousness. By remembering themselves during external and internal changes of clothes, practitioners of the noble path see that there is nothing either outside or inside which could be called “myself” or “forever mine”.

Taking Refuge in the Triple Gem

The Three keepers of Maitreya’s lineage (Dharmabhadra, the thief and the prostitute) embody, respectively, taking refuge in the triple gem (Buddha nature, the Teaching and Sangha).

The mind is concerned about three factors: 1) fear of loss, which comes down to fear of death 2) sensual thirst 3) darkened emotions, which are mental chewing gum.

From fear of death, we take refuge in our own unborn mind (Buddha). For the unborn mind, death — is a shallow stream it crosses without losing itself. We think about the unborn mind as blissful luminiferous emptiness that is unperplexed by anything. There are three steps to taking this view: 1) taking refuge in Buddha nature on the basis of authoritative opinions (of the Buddha, other sages and one's own teacher); 2) taking refuge in Buddha nature on the basis of conclusions arising from observations and practice (for example, the experiences which evidence the supremacy of energy over form; expansion of the consciousness; clairvoyance, etc. 3) taking refuge in the Buddha of our own mind as a result of developing supermundane wisdom. The point of all three steps — is remembering that the basis of the mind is permanent and steadfast.

From thirst, we take refuge in the Dharma. When beings unskillfully seek satisfaction in impermanent phenomena, ultimately this satisfaction turns into dissatisfaction. But Dharma brings continued satisfaction resulting from liberation from the triple thirst.

From darkened desires (mental chewing gum), we take refuge in the Sangha. Since in the Sangha we develop infinite feelings, which end darkened states, it is the Sangha which gives us refuge from desires. Whereas in communication with relatively distant people we often act like camels, spitting our mental chewing gum all over our interlocutor's face while fencing off from his or her feelings and thoughts, it is impossible to carry out this action in the Sangha. Here our chewing gum is already well-known to everyone, and for wholesome communication, we need something greater and more meaningful — openness and care.

Let good be!